Verloor Duc d'Alva zynen Bril

the Duke of Alva lost his spectacles!

When I set out to explore the highways and byways of time, I had no idea that tending bar would become such an integral part of my occupation. I knew a little astronomy, a little herbal medicine, a few odds and ends picked up from observing craftsmen at work, but next-to-nothing about how to flirt safely with carters and sailors, and how to manage a drunk. Well, little by little I'm filling in the gaps in my knowledge.

Having failed to locate Jan Sweelinck so far, it became necessary for me to find some short-term employment that would allow me enough leeway to continue my investigation; some free time is good, and plenty of interaction with Joe Public is vital.

Which explains why I am carrying pots of ale, the occasional mead (but we don't get much call for it these days) and making spiced wine in the kitchen here at the Neptunus inn. And this is where I was fortunate enough to engage Marten van Delft in conversation. Or rather, he snagged me as I was passing. He wasn't drunk, a little tipsy perhaps, and while he made a half-hearted pass at me, he wasn't serious about getting laid either. He just wanted someone to talk to.

Which explains why I am carrying pots of ale, the occasional mead (but we don't get much call for it these days) and making spiced wine in the kitchen here at the Neptunus inn. And this is where I was fortunate enough to engage Marten van Delft in conversation. Or rather, he snagged me as I was passing. He wasn't drunk, a little tipsy perhaps, and while he made a half-hearted pass at me, he wasn't serious about getting laid either. He just wanted someone to talk to.

Suited me fine! I recognized him as the boatman who had fitted his boat with wheels for the frost fair, and as it turned out, he had quite an illustrious career behind him as one of the notorious Watergeuzen, serving with the crew known as the Lost Child of Leyden. He recounts proudly the names of other crews as well, with names like the Great Thirst of Gorkum, The Cleaver of Alkmaar, and the Every Neck Forfeit, each of their names a reproach against Spanish atrocities.

He tells me the crews were a rag-tag mixture of disenchanted Spaniards, Frenchmen, English, Germans and Dutch, mostly mercenary buccaneer types happy to accept the nominal leadership of Prince William of Orange. It seems Prince William had issued very particular orders regarding ships sailing under his marque, but once at sea, the captains more-or-less made their own rules.

Every ship was to

- carry a priest.

- observe the Articles of War

- be commanded by a Dutch native

- accept neither soldiers or sailors unless they were men of a good reputation and respectable family.

Like all sailors, he can spin a good yarn, and at first I was disinclined to believe his story of the fleet led by Simon de Rijck blown off-course and forced to seek shelter in the harbor of Brijl where the ships' crews, impossibly outnumbered, surprised the Spanish garrison and recaptured the port. But I found out later, his tale wasn't embroidered all that much. Having misjudged the situation, the garrison force had been ordered to reinforce Utrecht.

The town gates had been locked and the militia turned out to man the walls while the town magistrates convened in the town hall. Captain Cornelis Roobol took a party of sailors and a length of mast timber and under fire from the ramparts of the wall, had his men lay tarred brushwood against the gates. Using black powder charges and fire to weaken the gates, the men finally managed to break the gates open using the battering ram and found the town largely deserted to the militia by the citizens who feared both the wrath of the Sea Beggars and the Spanish occupying forces.

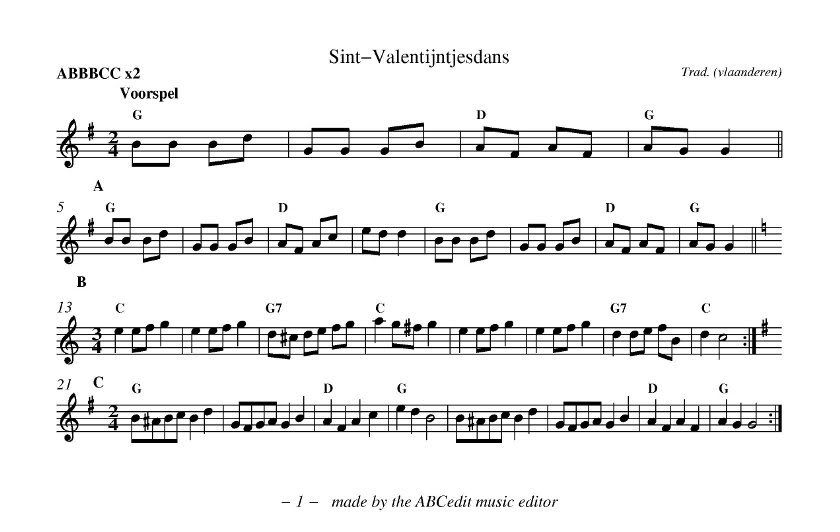

It was at this point that I interrupted Marten to ask him if he could teach me any of the sailors' songs. He knit his brows in thought for a few moments, blushed slightly and grinned, then taught me the following, which I doubt very much was regularly sung by the sailors (although You Know What Sailors Are!)

References

For anyone who wants to learn more about the Sea Beggars, or to get a better picture of piracy in the sixteenth century, I recommend this book, available online from Google Books or as a PDF for download to read at leisure.

I recommend also, this Gallery of Captains of the Sea Beggars

![]()

The written content of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

No comments:

Post a Comment