It's a few minutes before four o'-clock as I turn into the Langestraat and work my way down looking for number 19. The sun has already set and the light is fading, there are lights in most of the windows and it has been snowing lightly since three o'clock. For warmth I have my hands buried in a thick fur muff under the folds of my cloak.

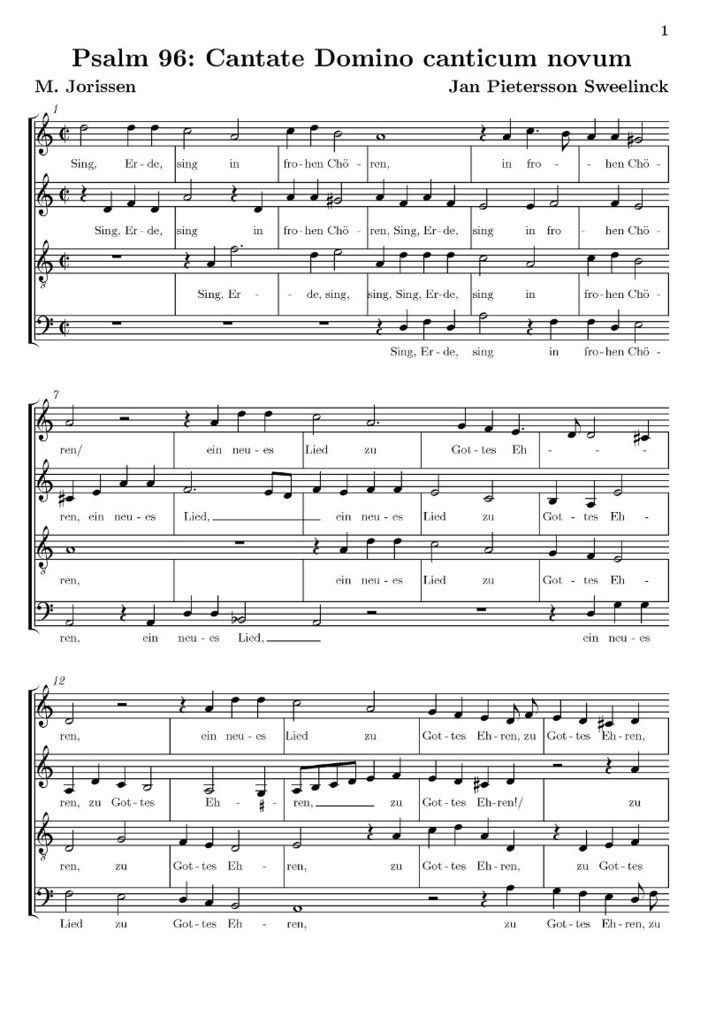

The Sweelinck house is just one in a street of tall, three and four-storey houses with wonderfully variegated gables, and the door, which opens directly into the downstairs conversatiekamer, is opened to me by a maid in plain brown dress, spotless white apron and cap carrying a small candle. She confers briefly with the occupants of the conversatiekamer before showing me inside where a beautifully decorated virginals stands close to the window taking advantage of the fading light, and three small candle lamps illuminate the rest of the room. On the opposite side of the window his mother, Elska Jansdochter Sweelinck is writing what I assume is a letter, and quite prominently placed on the wall is a largish print of King David playing the harp.

Jan seats himself with his back to the keyboard and asks me how he may be of service?

A bald question like that is a little like being at the site of a bomb going off! There are so many things I would like to ask, but the key to my mission is to collect and disseminate music which is in danger of being overlooked in favor of the new and gaudy. But to this, I make no overt reference. Instead, I explain that, as a working woman I cannot afford to pay him for regular lessons, but would be very grateful if he would let me observe his playing of a few pieces, and perhaps assess my own playing?

He looks thoughtful for a minute before suggesting that I seat myself and play something for him to observe me!

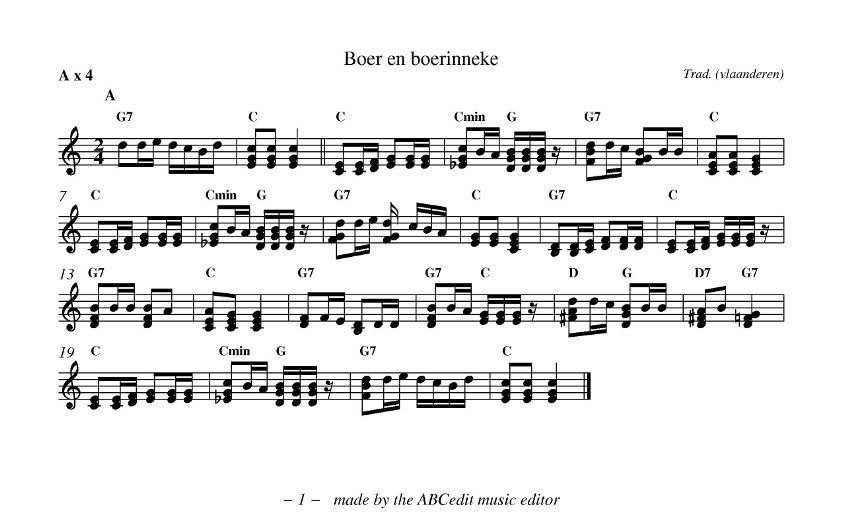

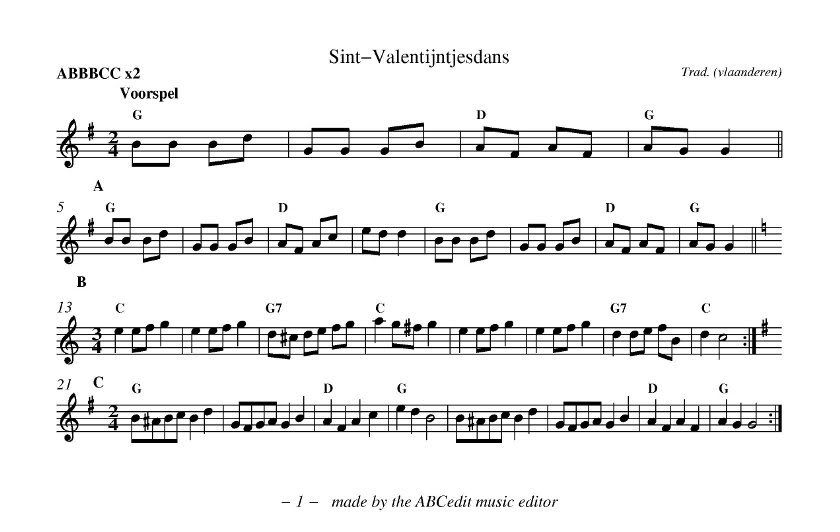

Shuffling through the manuscripts on the music stand he picks out an easy dance and gestures for me to start. I could hardly be more nervous if I was facing the Duke of Alva himself!

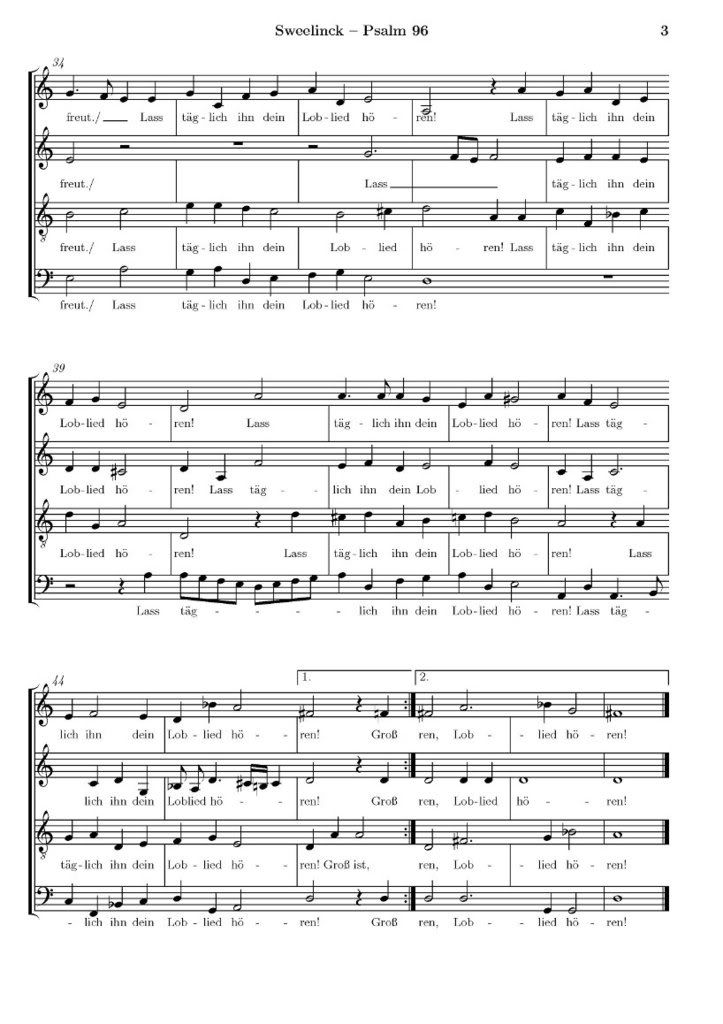

It is difficult to concentrate on reading the unfamiliar mensural notation and not surprisingly, I stumble repeatedly. But Jan surprises me when, at the end of the piece, he asks me to stand once more, and observe how he plays it.

The first thing I notice is that he is using the index, middle, and ring fingers of his right hand, only dabbing occasionally with his thumb or pinkie to ornament the line. And looking round at me with a grin, he even imitates one of my stumbles!

It is quite clear, even before he comments on my clumsy fingering, that I should either seek a good tutor, or consider learning to play a different instrument.

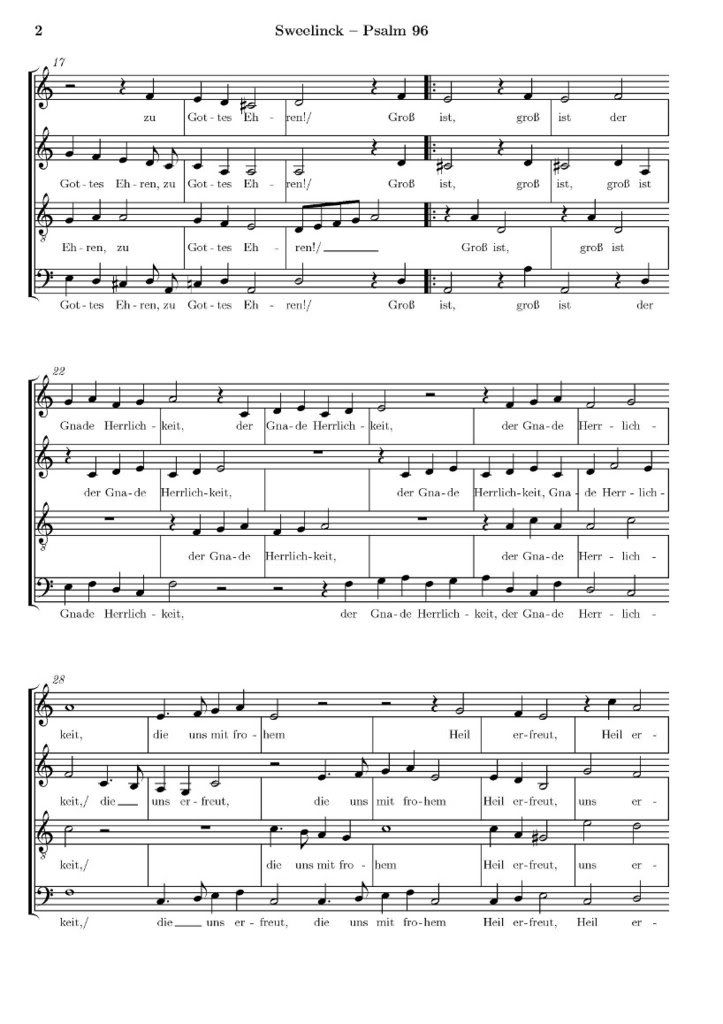

I am quite taken aback by the astonishing hospitality of the family when I am invited to join them for dinner, since the hour is approaching. For a middle-class family like themselves to consider entertaining a grauw servant like myself requires the abnegation of social boundaries but in the conversation that accompanies the meal they make it clear that my cover story is failing and they are well-aware that I am not an uneducated peasant! In the course of the meal, which compared to my fare of the last few days is nothing less than a feast, I have opportunity to learn more in depth about the occupation of the Netherlands, and Jan's musical skills, inherited from, and carefully nurtured by his late father, the previous organist at the Oude Kerk.

In a final desperate attempt to avoid questions that would expose me, I have hinted very broadly that I am gathering intelligence (true enough), though whether for Prince William, or another friendly power (or even for the Duke of Alva) I have tried not to suggest. Taking my leave, and thanking them for their generous hospitality, it is very definitely time for me to leave!

To learn more about Amsterdam in the 16th century I encourage you to visit the following sites:

How to play the virginals like Jan Sweelinck

Domestic life in 16th century Holland

The written content of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

In my free afternoon, I make my way to the Kerk through the icy streets. The Kerk is every bit as huge and draughty as I expected but in the

In my free afternoon, I make my way to the Kerk through the icy streets. The Kerk is every bit as huge and draughty as I expected but in the

Which explains why I am carrying pots of ale, the occasional mead (but we don't get much call for it these days) and making spiced wine in the kitchen here at the Neptunus inn. And this is where I was fortunate enough to engage Marten van Delft in conversation. Or rather, he snagged me as I was passing. He wasn't drunk, a little tipsy perhaps, and while he made a half-hearted pass at me, he wasn't serious about getting laid either. He just wanted someone to talk to.

Which explains why I am carrying pots of ale, the occasional mead (but we don't get much call for it these days) and making spiced wine in the kitchen here at the Neptunus inn. And this is where I was fortunate enough to engage Marten van Delft in conversation. Or rather, he snagged me as I was passing. He wasn't drunk, a little tipsy perhaps, and while he made a half-hearted pass at me, he wasn't serious about getting laid either. He just wanted someone to talk to.

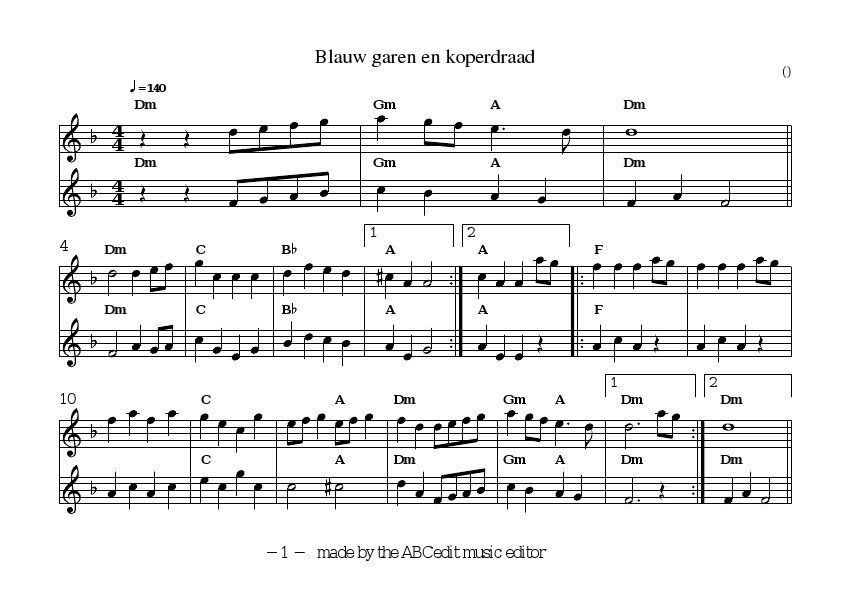

And all of this had the effect of diverting me from my goal of finding Jan Sweelinck. However, the excursion wasn't completely fruitless, as I spent several hours in the evening getting some of the chill out of my bones beside the fireplace in one of the city's many taverns, and got to know for the first time, an instrument which is really very common, which makes it surprising that I hadn't met it before: the

And all of this had the effect of diverting me from my goal of finding Jan Sweelinck. However, the excursion wasn't completely fruitless, as I spent several hours in the evening getting some of the chill out of my bones beside the fireplace in one of the city's many taverns, and got to know for the first time, an instrument which is really very common, which makes it surprising that I hadn't met it before: the