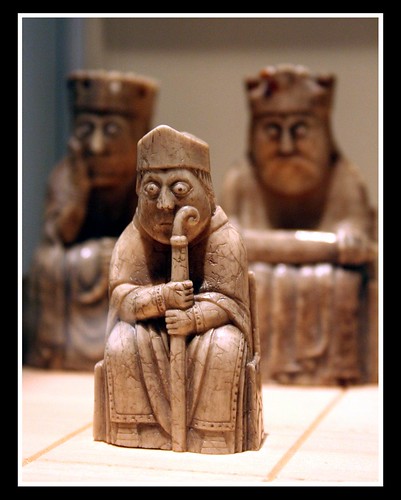

"For he who sings praise, does not only praise, but also praises joyfully; he who sings praise, not only sings, but also loves Him whom he is singing about/to/for. There is a praise-filled public proclamation in the praise of someone who is confessing/acknowledging (God), in the song of the lover (there is) love."Whenever I see John of Salisbury, Bishop of Chartres, I can't help thinking of the Bishop from the Lewis chessmen. A stocky saxon nobleman, with a permanently fixed distracted expression as if he's always in conversation with someone hiding under his mitre, but lively, ice-blue eyes, a firm handshake, and those extraordinary brightly-colored clerical robes.

The reason I sought out the Bishop was to learn more from him about the practice of singing organum which is rapidly gaining popularity in the church community. Since the earliest days of the established church, song has been an integral part of worship, but until recently the singing was limited to the style which eventually became known as Gregorian chant, although there is no solid connection between the tradition of an unaccompanied choir singing a melody in unison. In the year we are visiting, 1179, opinions are still divided over the question of whether chant should be in blessed unison or heavenly harmony.

In conversation with one of the Deans of the Université de Notre Dame here in Paris, the Bishop expressed his opinion which seems to favor continuing progress with careful moderation:

"When you hear the soft harmonies of the various singers, some taking high and others low parts, some singing in advance, some following in the rear, others with pauses and interludes, you would think yourself listening to a concert of sirens rather than men, and wonder at the powers of voices … whatever is most tuneful among birds, could not equal. Such is the facility of running up and down the scale; so wonderful the shortening or multiplying of notes, the repetition of the phrases, or their emphatic utterance: the treble and shrill notes are so mingled with tenor and bass, that the ears lost their power of judging. When this goes to excess it is more fitted to excite lust than devotion; but if it is kept in the limits of moderation, it drives away care from the soul and the solicitudes of life, confers joy and peace and exultation in God, and transports the soul to the society of angels..."I was also surprised and delighted when I learned that in his youth, the Bishop was a student here himself, under the tutelage of Pierre Abelard, famed forever in the story of Abelard and Heloise!

For the students here in Paris, this is an age of wonders. A time when the glory of God seems almost tangible, the Kingdom of God is certainly at hand, and anything might be possible. And even hiding behind the persona of one of the Bishop's retinue, I can feel the tide of excitement surging as young men engage in lively debates in the taverns nearest to the schools of the Université, and learned doctors speculate on ways in which the majesty of the Creator is revealed in His creation.

Undoubtedly the most exciting evening of my own visit here is attendance at an evening service in the cathedral at which the Bishop will officiate; the music the choir is singing is an organum triplum composed by Magister Perotin.

Perhaps it is because they are used to helping students to answer queries, that when I approach the Bishop with my question about the beginnings of organum singing, not only does he answer me from his own experience, but he also tows me along through the huddle of worshippers to ask Magister Perotin himself!

Between the two of them I manage to understand that as early as the ninth century, choirs had begun to embellish the music on special occasions by dividing into two groups, one group singing tenor, the plain melody, and the other singing the same melody at a fourth, or fifth above, or below. And although there is a new development being tried experimentally by some choirs, the organum contrarium, in which the tenor is inverted by the vox organalis, the Bishop is not as enthusiastic for it as he is for Perotin's organum duplum and triplum.

Magister Perotin asks me whether I can read (have you ever tried reading a medieval manuscript? in latin, too); the library of the Université contains copies of the treatises Ad Organum Faciendum, (To Make Organum) and Musica Enchiriadis. As much as I would love to stay and study the manuscripts, I worry that my ineptitude as a reader might provoke too many questions about my background, and not for the first time, I find myself confounded. While the technology of my native time has made it possible for me to explore history, it has not provided me with any better recording media than my own brains.

I should mention that I didn't learn until almost I was ready to return to my own time, that Magister Perotin is well into his eighties, but I would have guessed his age to be roughly contemporary with the Bishop. Like Moses, his eye was not dimmed, nor his natural force abated!

In Memoriam: Midnight_In_Gethsemane 1953-2008 Between the two of them I manage to understand that as early as the ninth century, choirs had begun to embellish the music on special occasions by dividing into two groups, one group singing tenor, the plain melody, and the other singing the same melody at a fourth, or fifth above, or below. And although there is a new development being tried experimentally by some choirs, the organum contrarium, in which the tenor is inverted by the vox organalis, the Bishop is not as enthusiastic for it as he is for Perotin's organum duplum and triplum.

Magister Perotin asks me whether I can read (have you ever tried reading a medieval manuscript? in latin, too); the library of the Université contains copies of the treatises Ad Organum Faciendum, (To Make Organum) and Musica Enchiriadis. As much as I would love to stay and study the manuscripts, I worry that my ineptitude as a reader might provoke too many questions about my background, and not for the first time, I find myself confounded. While the technology of my native time has made it possible for me to explore history, it has not provided me with any better recording media than my own brains.

I should mention that I didn't learn until almost I was ready to return to my own time, that Magister Perotin is well into his eighties, but I would have guessed his age to be roughly contemporary with the Bishop. Like Moses, his eye was not dimmed, nor his natural force abated!

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Szmytke of Flickr, for permission to use the image of the Lewis chessmen, and the M.A.B. soloists and M.Moriwaki for their transcription of Perotin's organum, shown above.

The written content of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

The written content of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

No comments:

Post a Comment