When I learned at school about the history of the slave trade, I was taught how unscrupulous western merchants trapped, enslaved and sold African natives, in the most barbaric conditions, giving little thought to the welfare of the men, women and children that they sold, but concerned above all to turn a profit. So it came as quite a surprise to hear another side to the story altogether from Mr.Alexander Stewart, Scottish expatriate in France, in 1752.

Having not paid too much attention during my schooling, I was marginally aware of the events of the two great Jacobite rebellions against English rule, the ‘15 and the ‘45, but I have no recollection of being taught more than the most rudimentary facts concerning the aftermath of the terrible Battle of Culloden at which the Young Pretender, Charles Edward Stuart, was trounced.

To set the scene: the Lowland Scots, a people culturally apart from the Highlanders, favoured political union with England under the reign of Queen Mary and Prince William of Orange, recently arrived from the Netherlands. However, the Highland Scots still pledged their allegiance to the House of Stewart despite the desperate haste with which King James the VII of Scotland, and II of England fled from the advance of the Orange forces during the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

The highland Scots saw their way of life threatened and in hope of some measure of security, lent their support to the exiled young prince Charles Edward Stuart, Bonnie Prince Charlie, grandson of James VII. The rebellion was short-lived. On July 23rd, 1745, the prince landed on the Isle of Eriskay to begin raising support for his campaign to reclaim the throne. Ten months later, on April 16th, 1746, seeing his army outgunned and outmanned the Young Pretender fled the field of battle, at which point I let Alexander Stewart take up his account:

After his royal highnes came over the Water of Nairn, after the battel, escorted by a partie of the Fitze James's horse, his highnes went to the right of the highway that leads to Ruthven of Badenoch. I having the cantains behinde me, I went a little of the highway after his highness, and asked his highness if he would be pleased to take a refreshment of any thing, as he hade not eate nor drunk any thing that day.

His highness reply to me was, ‘Stewart, no meat no drink;’ but desired me to go on the highway to Ruthven of Badenoch and the Fitze Jamess horss would escorte us, which I went, but with a sorieful heart to parte with my royal Prince and master, ... about two aclok in the afternoon, ... his Grace, the Duke of Perth, and Lord John Drummond cam upe to us. So they consulted that everie man should doe for himself and God for us all, which accordingly we all disperseed, and everie on took his own way, and I went southward till I came to Mr.Rattrays of Craighall, ... till on Reid, a Justice of the peace, came their to dine, and beged of Mr.Rattray that he would not give quarters or entertainment to any of those men called rebells, for which Mr.Rattray came after and told me after dinner that he was not safe to keep me any longer about his house.

So I went directly away to Mr.Rattray's of Rannegoolen ... And about two o'cloke in the morning Sir James Kinloch and his two brothers and Mr.Rattray and his brother in law and three servants of us was all taken by a pairtie of the Queene of Hungaries hussares, commanded by a cornell, a Pollander he was, but I never could know his name ... And from that we was taken away to Couper of Angus, ... where I served the table the time of dinner, and the cornell, when he asked a drink or bread in French, I went and gave it to him directly. For so doing he tooke me to be a Frenchman, because I served it to him readily; for which he asket Sir James what I was, or if I was a French-man? and Sir James told, without asking me, that I was a servant to Mrs.Murray, the Secretares lady; ... And after dinner their was horsses prepared for the gentlemen and a cart for us three servants, and from that we was cairried away to Perth, and taken to the Prince of Hess quarters, and was examened by him and the Duke of Athol and the Earle of Crafoord, and several other gentlemen that I did not know; but on of them that they called Cornell Stewart, who came upe to me and asket what was my name. I told my name was Stewart. So, says he, my lad, you dont think proper to deny your name for all that's done. I have done nothing as yet, Sir, says I, dishonourable but served my master, for which I have no reason to deny my name. And he went away sueiring and lughing to the dor, and the Prince of Hess say to him, ‘Poor gentlemen, I am sorie for their misfortunes.’

Then we were all cairried from that to Mr.Hicksons untill George Miller, that common hangman, the sheriff clerk of Perth, should be found, because he was out of the way at present; and their we stayed about a quarter of ane hour, and then Miller came and we were all taken away to the Councell chamber, and the said Miller examened us all, and then we were all put upe into prison by his orders and remained their in Perth goal untill the ninth of Agust following.

So last of all Mr.David Bruce, commenly called Judge Advocate, came to Perth, and we was all called on by on and examened by him. Then [he] asked me if I knew any of those men that was standing their? I told them I had the misfortune to know them too weel since they and me hade been in prison together, but never before.

‘Weel,’ says Bruce, ‘you will not know on another heir, but I shall cause cairrie you to Carlisle, and caus the on of you hang the other.’

I told him I would defye him or any one to doe so, for if I was to be hanged I should hang no man but myself. However he said he would try for it, which accordingly he dide to the fatal experience of many a brave fellow.

After this, the prisoners of war were roped together in pairs and marched through Falkland, Lintoun, the Kirk of the Beild, Moffat, Lockerby and Gretna Green to Carlisle, being joined by the prisoners from Stirling at around noon.

... about two a clock in the afternoon a rascall of the name of Gray, Soliciter Hume's man from Edinburgh, with his hatful of tickets ... presented the hat to me, being the first man on the right of all the twentie that was to draw together. I asked Gray what I was going to doe with that, and he told me it was to draw for our lives, which accordingly I did, and got number fourteen. So he desired me to look and be sure. I told him it was no great mater whether I was shure or not. ... And betuixt five and six a clock at night Web, Miller, and Gray, and on Henderson, came all out to the yarde, where we was sitting on the grass, with a verie large paper like a charter, and read so much of it to us as they thout proper, and told us that it was to petition their king (George I) for mercy to us, and that it was to go of that night for London, and as soon as it came back we might probably get hom, or els transportation, which would be the worst of it; ...

Now the men were marched from Carlisle through Penrith, Kendall, Lancaster, Preston, Ormkirk and finally to Liverpool on April 30th, 1747 where they boarded two ships.

The names of the two ships was the Gillder and Johnstoun, both belonging to Gillder, member of parliament for Liverpool, and their was eighte eight of us in the shipe called the Gillder, Richard Holms, captain, and Robert Horner, supercargor, a Yorkshire byt. When we went aboard we wer all stript and searched that we hade no armes about us, or any instrument for taking of our irons, and thene we put on our cloths again, and then we was desired to go aft to the steirreg until we got on the Hanoverian pleat on our leags, and went to se the apartment where we was to ly.

The ships put to sea on May 18th, but a violent storm on the 22nd separated the flotilla until the Gillder reached the inlet mouth between Cape Charles and Cape Henry, at which point a Spanish ship gave pursuit, but could not catch the ship before they entered American waters.

So being got within the river, our supercargor and the Doctor went to take their rest, and our Captain came and sat down on the trap that came down between dakes and discours'd us, and asked us what we was to doe now when we was near our journey's end. ... So when we came up forgainst St.Maries, the Captain went ashore, it being the pleace where the Custom hous was, that he might enter us all their, and in two or three hours time he came aboard again, and caused the carpenter go and take of all our irons, which accordingly was done. ... And that night being Sunday the 19th of Jully 1747, we came to ane ancor at the port called Wecomica, where we was to be put ashore at, and as soon as the shipe came to ane ancor, we was all ordred below dake, for Robert Horner, the supercargor, wanted to speak a queet word to us, which accordingly went all doun between daks, and Horner came doun and made a verie fine speach concerning the goodness of the countrie that we was going to; and if we would atest for seven years, the men that would by us, if we pleased them weel, would probably give us doun two years of our time, a gun, a pick and a mattock, and a soot of cloths, and then we was fre to go thorou any place of the illand we pleased.

And so away ashore with the Captain he went that night, for our Captain's wiffe lived about a mill and ane half from the shipe, and from that Horner hade about ninteen milles to go where the Governor lived to Annapolis; and the time he was there our Captain sent letters to all the Romman Catholick gentlemen and others, who was our friends, so that we might not fall in the common buckskin's hand, for so the people that are born their are called so.

So as I told you befor that Captain Holms acquanted all the gentelemen of three or four counties of the province of Maryland to atend on board the day of the sale, which hapned one the 22d of Jully 1747, after the shipe came to ane ancor at Wecomica, in St. Mary's countie, Maryland, who bought all the eightie eight that was aboarde of our shipe except thre or four that went with two of the common buckskins, ... and would not take advice to go allong with the above gentlemen.

Doctor Stewart and his brother, William, both living in Annopolis, and both brothers to David Stewart of Ballachulan in Montieth, Scotland, who were all my loyal masters fast friends, and paid the nine pound six shillings sterling money that was my price when sold to Mr. Benedict Callvert in Annopolis, who is a verie pretie fellow, and on who hade my being set at libertie at heart as much as any man in the province.

Being now a free man once more, Mr.Stewart sought the household of Mr.Edward Digs, one of the gentlemen who had helped buy the freedom of Stewart and his compatriots and ...

...stayed there untill Mr.John Mushet found out ane honest man, a captain of a shipe (called the Peggie of Dumfries) bound for Dumfreece, ... and the 11th of January 1748 I took my livee of all my friends, and went aboard on the 13th of the said month, but our cargo not being all got ready so soon as was expected, it was the 28 befor we set saill to fall down the river towards the Capes, and being within 3 leags of the Capes we was obliged by ane easterly wind to put in to Hampton Road and their we dropt our ancors and lay for 12 days, and on the 13th of February 1748 about two in the morning we got cleare of the Capes and put to sea and befor daylight we got out of the sight of land, and in 27 days we saw the Irish land;

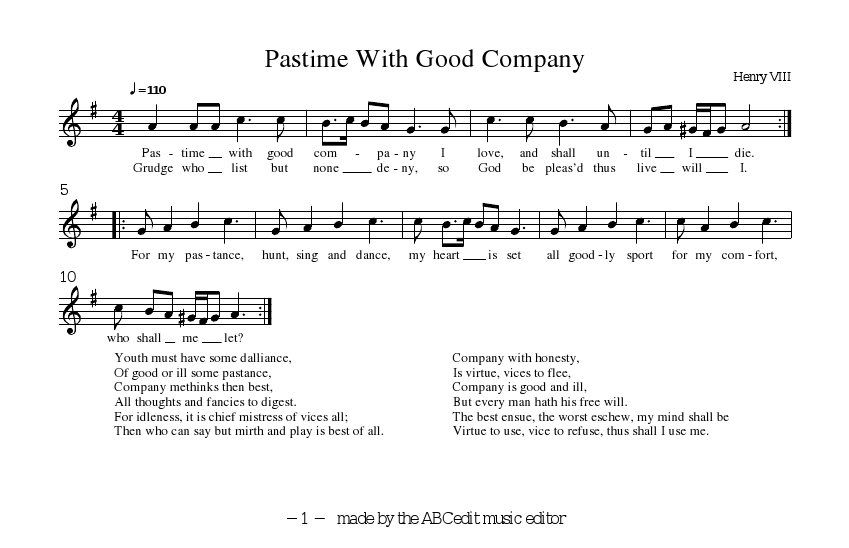

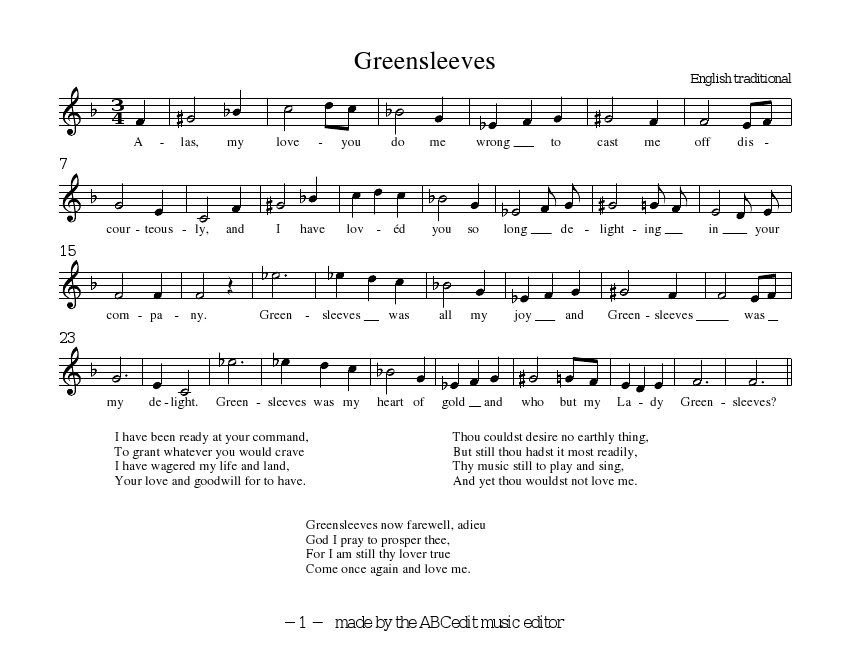

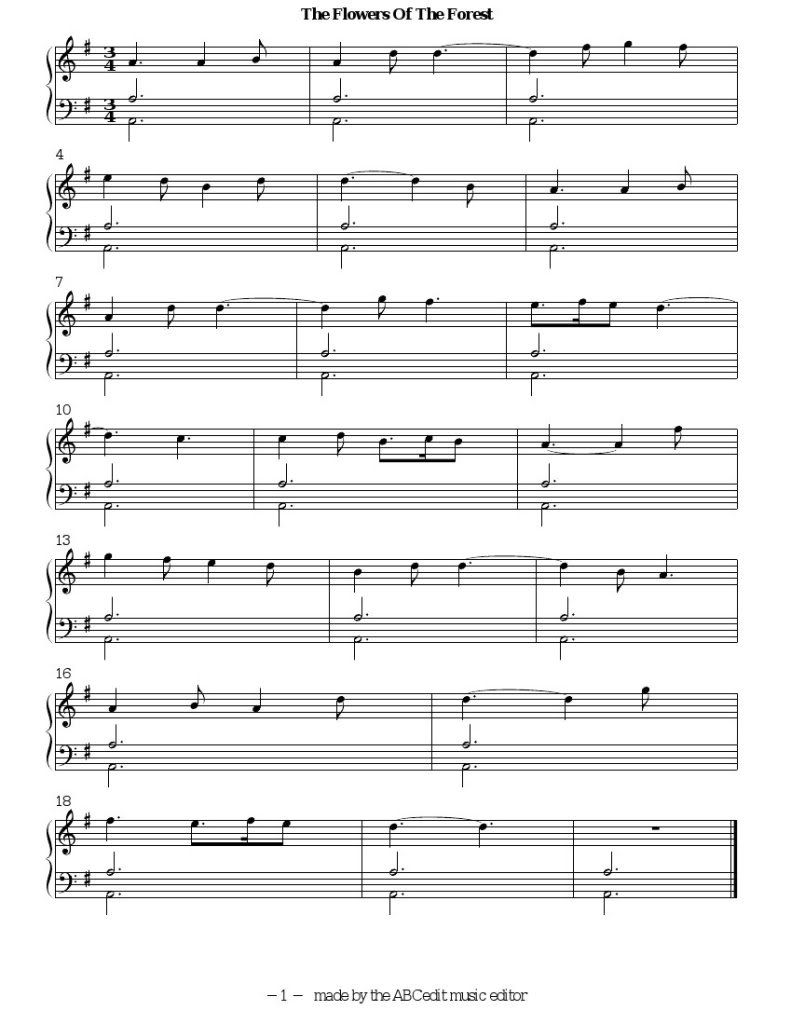

As a tribute to the brave young men who died that day on Culloden moor, and those who were later put to death for their part in the uprising, I am including a score of the traditional Highland lament The Flowers of the Forest.

References

The full account of Alexander Stewart's capture as a prisoner of war, and subsequent transportation and sale as a slave is told in his own words, in Vol. II of The Lyon in Mourning

This map shows the approximate route taken by the prisoners and escort, to Liverpool docks for transportation.

The written content of this work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.